Talent Acquisition & Retention: Why Growth-Stage Companies Hemorrhage Engineers and Lose Cultural Identity

Why 82% of growth-stage companies struggle with talent, and how to fix the hiring velocity trap.

When a growth-stage company enters the rapid-scaling phase, the founder’s first instinct is to hire aggressively. The startup has achieved product-market fit, revenue is growing, and the mandate is clear: scale the team to capture market opportunity before competitors do. Yet this instinct creates a cascade of cascading failures that systematically destroys both company performance and cultural identity.

The data is unambiguous. In a comprehensive survey of 50+ growth-stage companies (Series B-D), 82% identified talent acquisition and retention as their most critical operational challenge—ranking it above product development (45%), fundraising (35%), and go-to-market execution (28%). This isn’t a peripheral HR concern. For CTOs, executive teams, and founders responsible for engineering velocity and product delivery, talent acquisition dysfunction represents an existential threat to company trajectory.

The problem manifests across multiple dimensions simultaneously: companies hire rapidly without ensuring cultural fit or skill alignment, onboarding is chaotic and cultural values decay, critical technical roles sit empty despite aggressive recruiting, early employees promoted to management roles collapse under responsibilities they’re unprepared for, and institutional knowledge evaporates when key technical leaders burn out and depart. The result is a company that has grown headcount 50% but experienced a 30% decline in engineering productivity, cultural coherence has fractured, and the retention cliff accelerates as senior engineers recognize the deteriorating environment and leave.

For founders, CTOs, and investors responsible for engineering effectiveness and company trajectory, understanding why talent acquisition dysfunction emerges at scale, how it destroys value, and what leadership models actually work has become essential to competitive performance.

Why Talent Chaos Emerges: The Root Causes of Growth-Stage Scaling Failure

Talent acquisition dysfunction doesn’t emerge from a single management failure—it’s the inevitable byproduct of how growth-stage companies evolve when structure and discipline don’t keep pace with scale.

The Hiring Velocity Problem: Quantity Over Quality

When a growth-stage company closes a Series B at $10-20M ARR with 3-6 months of runway, the pressure to hire is existential. The sales team has closed logo deals; the product roadmap requires 3 additional engineers to execute; the infrastructure is buckling under load; and the CTO’s mental model is: “We need 10 engineers, and we need them in 60 days.”

This creates a fundamental misalignment between recruitment speed and hiring standards. The process that took 3 months pre-Series B (2-3 technical interviews, reference checks, cultural assessment, onboarding plan) compresses to 3 weeks (one technical screen, a manager interview, verbal offer). Candidates who would have been rejected 6 months earlier are hired because they’re available and “close enough” to the required skill set.

A typical series B hiring scenario: The CTO posts a job for a “Senior Backend Engineer.” Three weeks later, after interviewing 12 candidates, they hire a candidate with:

- 4 years of experience (the role sought 6+ years)

- Experience in a different technology stack (Node.js background for a Go-heavy codebase)

- No prior experience with the company’s cloud infrastructure (AWS)

- Personality indicators suggesting individual contributor preference, yet the team needs someone who can mentor juniors

The hiring manager acknowledges the gaps but rationalizes: “We’re hiring for potential. They can learn. We can’t wait another month.” Six months later, the hire struggles, requires significant mentoring from already-overloaded senior engineers, and eventually leaves. The company has consumed 3 months of a senior engineer’s mentoring time, created cultural frustration around hiring standards, and now must re-recruit the role.

This pattern repeats across dozens of hires in a 12-month growth-stage scaling cycle. A company that hires 30 engineers across Series B realizes later that 8-10 of those hires were “miss-hires”—people who weren’t fundamentally wrong for the role but weren’t right-fit, creating downstream friction.

The cost of miss-hires is substantial. The Society for Human Resource Management estimates the fully-loaded cost of replacing an employee at 150-200% of annual salary when accounting for recruiting, onboarding, lost productivity, and knowledge transfer. For a $150K engineer, a single miss-hire costs $225-300K. For a company with 8-10 miss-hires annually, this represents $1.8-3M in destroyed value per year.

Yet the hiring velocity problem extends beyond miss-hire cost. It creates cultural degradation. When a company hires 30% of its headcount in a 12-month period without rigorous cultural and skill-fit assessment, the hiring cohort dilutes the company’s cultural identity. New hires don’t understand why the company operates the way it does. Founders’ statements about “moving fast” or “we’re customer-obsessed” aren’t embodied in systems and decisions—they’re just words. Cultural norms shift as critical mass of new employees normalize lower standards than founders intended.

The Onboarding Charade: Hiring Without Preparing to Absorb

Growth-stage companies understand that onboarding matters. They typically allocate 2-4 weeks of onboarding to new engineers: access to repositories, AWS credentials, CI/CD pipeline walkthrough, introduction to the team, documentation review.

Yet this “onboarding” is categorically different from the preparation required to absorb a new hire into a rapidly-scaling technical organization. A better term would be “access provisioning.” It provides access but doesn’t develop competency.

Effective onboarding for a growth-stage company should include:

- Technical orientation: Deep walkthroughs of architecture, data models, deployment processes, monitoring infrastructure. Not the 2-hour overview but the 20-hour deep dive that enables independent problem-solving. This typically requires dedicated mentorship from a senior engineer for 40+ hours across the first month.

- Codebase mastery: Reading and understanding how the existing codebase works, making small contributions, receiving code review feedback, understanding why certain architectural decisions were made. This requires an additional 60+ hours of mentorship across the first two months.

- Organizational context: Understanding how engineering connects to product, sales, finance, operations. Who are the key stakeholders? What are the current strategic priorities? What is the company’s growth story? What were the key engineering decisions that shaped current architecture? This context transfer requires 10-15 hours of leadership attention in the first month.

- Cultural integration: Participating in company rituals, understanding informal norms, building relationships across teams, socializing outside of work context. This is passive but critical—it happens through regular interaction with peers and leaders.

For most growth-stage companies, the actual onboarding experience is dramatically truncated. New engineers receive repository access, sit down with the codebase, struggle for 2 weeks to understand context, are thrown into a sprint by week 3, and are expected to contribute meaningfully by month 2. Senior engineers volunteer to answer questions but are overloaded with their own work. No one has been explicitly assigned onboarding responsibility. The CTO is in 15 meetings a day and doesn’t have time for context-setting conversations. Documentation is sparse or outdated.

This creates a coherent pattern: 30% of new hires in growth-stage companies report feeling disoriented after 3 months, struggle to understand the codebase after 6 months, and either leave or develop workarounds that increase technical debt (they build new components rather than learning to modify existing ones because the existing codebase feels impenetrable).

The onboarding failure has a compounding impact on company architecture and velocity. When new engineers don’t understand existing architecture, they build redundant components. When they don’t understand why decisions were made, they second-guess architectural choices and propose rewrites that consume months of time. When they’re not integrated culturally, they operate as individuals rather than team members, reducing cross-functional collaboration and mentorship.

The Promotion-Into-Management Trap: Creating Ineffective Managers

Growth-stage companies face a specific talent problem: they need engineering managers but can’t afford to hire them externally. A startup with $30M ARR and 50 engineers needs 4-5 engineering managers. Hiring managers externally is expensive ($150-250K salary + benefits + 3-month search) and creates cultural friction—external hires don’t understand company history or culture.

The rational path forward: Promote early employees into management roles.

The first engineer who joined pre-Series A is promoted to “Tech Lead” and then “Engineering Manager.” The second engineer, when a second team is created, becomes Engineering Manager for that team. This seems natural—they understand the codebase, they understand company culture, and they have credibility with peers.

Yet promoting early technical employees into management roles without preparation is one of the highest-impact ways to destroy engineering culture and velocity. Here’s why.

Technical excellence (the primary driver of early-stage hiring and promotion) is uncorrelated with management capability. The engineer who excelled because she was obsessive about code quality, architecture rigor, and personal accountability may be terrible at delegating work, developing people, and making group decisions. The engineer who was a prolific individual contributor may lack the emotional intelligence or patience for mentoring junior engineers. The engineer who thrived in a startup environment where autonomy was unlimited may struggle with the reduced individual contribution when management consumes 60% of her time.

Without management training, early promotions into management create predictable failure patterns:

- Micromanagement: Technical managers who are accustomed to executing work themselves often struggle to trust that others will execute with the same rigor. They hover over implementation decisions, provide excessive direction, and reduce team autonomy. Junior team members feel suffocated; independent engineers feel disrespected.

- Lack of strategic perspective: Technical managers promoted from individual contributor roles haven’t developed strategic thinking. They execute the work their managers assign but don’t proactively identify company-level strategic opportunities or anticipate future technical needs. They’re executing managers, not leadership-caliber managers.

- Poor hiring and team-building decisions: Technical managers often promote hiring decisions in their own image—they look for engineers who think like them, operate like them, and have similar technical preferences. This reduces team diversity and creates monocultures. They’re also likely to promote other early employees into roles for which they’re unprepared, replicating the promotion problem.

- Absence of people development: Technical managers are often uncomfortable with difficult conversations (performance feedback, recognition, compensation discussions). They avoid these conversations, creating situations where mediocre performers aren’t coached to improve, high performers don’t get feedback or recognition, and frustration accumulates.

- Decision-making without context: Early technical managers make decisions (architectural choices, technology direction, hiring) without understanding business context. They optimize for technical purity rather than business velocity. They choose technologies because they’re technically superior rather than because they solve business problems faster.

In a growth-stage company with this management pattern, you see a consistent phenomenon: high technical talent leaves because the management environment became intolerable, mid-level talent stagnates because managers don’t develop people, junior talent is confused about company direction and leaves after 18 months, and the company’s engineering culture shifts from “we’re a place where great engineers thrive” to “we’re a place where you’re expected to figure it out yourself.”

The Institutional Knowledge Evaporation Problem

Growth-stage companies operate in permanent beta. Architecture decisions that made sense at 10 employees may be wrong at 50 employees. Technology choices that were optimal at $1M ARR become problematic at $20M ARR. The early technical team (the CTO, the first 3-5 engineers) understood why decisions were made. They have institutional memory about past architectural choices, failures that taught hard lessons, and the evolution of the company’s technical strategy.

When these early employees leave—which happens with increasing frequency as management environments deteriorate, compensation becomes misaligned, or founders decide they need “outside expertise”—the company loses not just the engineers but the institutional context. New engineers inherit decisions that they don’t understand. The company has Docker Compose-based development while production runs Kubernetes, but no one knows why that split happened or what attempted migration failed 2 years ago.

This knowledge evaporation creates cascading technical debt. New engineers second-guess existing decisions because they don’t understand the reasoning. They propose rewrites of “legacy” systems that were actually well-designed for their constraints. They build new components rather than extending existing ones because they don’t understand what exists. Within 3-5 years, a company that had coherent architecture deteriorates into fragmented complexity that no individual fully understands.

The productivity impact is substantial. A company with coherent architecture and knowledge transfer can achieve 3-4x the velocity of a company with fragmented knowledge and deteriorating architecture, even with the same headcount.

The Value Destruction Cascade: How Talent Dysfunction Erodes Growth-Stage Company Performance

The impact of talent acquisition and retention failures compounds across multiple dimensions that accumulate over 3-5 years.

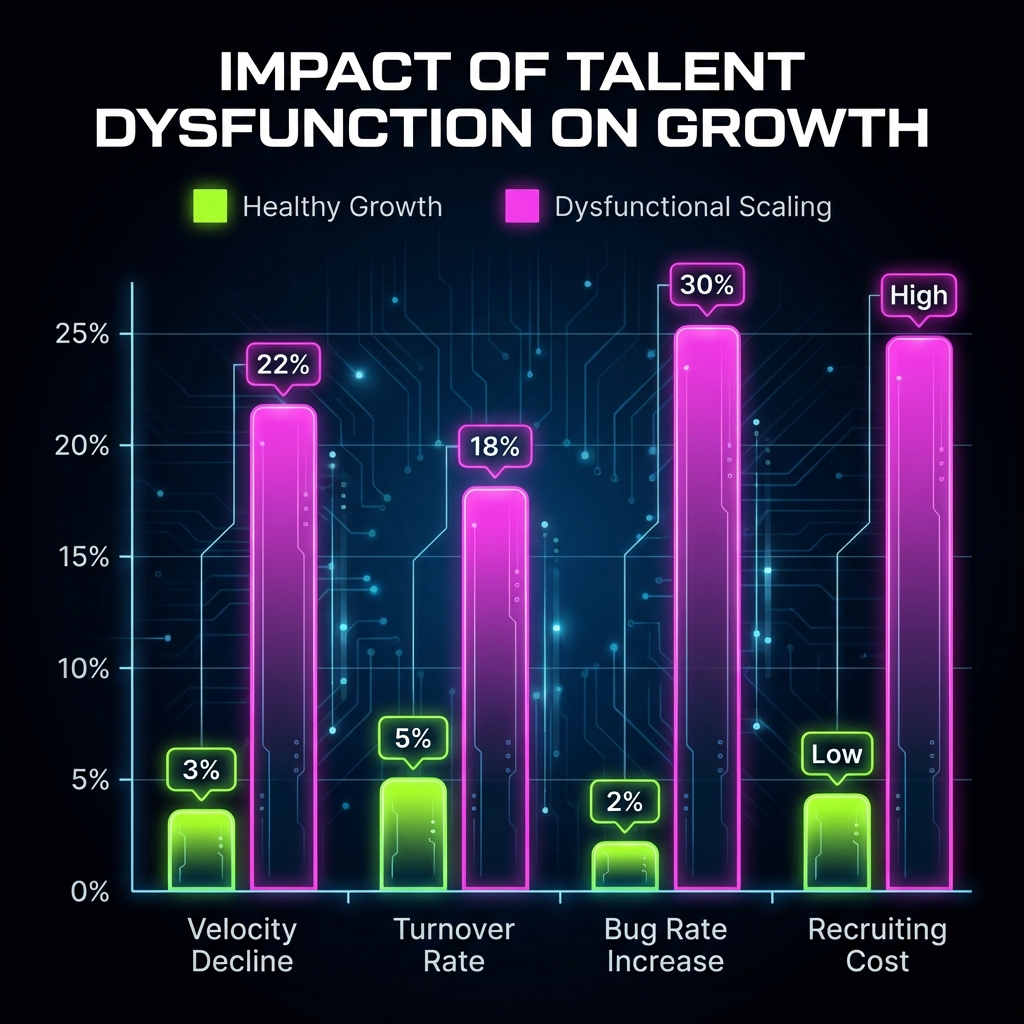

Velocity Degradation: The Productivity Tax on Poor Hiring

The most immediate impact: engineering productivity declines despite increasing headcount.

A typical pattern in growth-stage companies:

- Series A (12 months prior): 8 engineers, shipping 3-4 major features per quarter, velocity relatively consistent

- Series B close: 8 engineers still (hiring takes time), same 3-4 features per quarter

- 6 months post-Series B: 18 engineers hired, velocity drops to 2-3 features per quarter (30% decline despite 125% headcount increase)

- 12 months post-Series B: 25 engineers, velocity drops to 1-2 features per quarter (50% decline despite 200% headcount increase)

This counterintuitive pattern—rising headcount, falling velocity—happens consistently in growth-stage companies that haven’t solved hiring and integration discipline.

The root causes accumulate:

- Onboarding tax: When a company adds 15 engineers in a 6-month period, existing engineers spend 20-30% of their time onboarding, answering questions, and providing mentorship. For a company with 8 engineers, this represents 3-4 FTE devoted to onboarding rather than feature development.

- Knowledge fragmentation: New engineers operating without deep codebase knowledge build redundant systems, make architectural decisions others have to undo, and create technical debt that senior engineers must eventually remediate. The company’s velocity becomes 70% new feature work, 30% remediation of miss-hires’ technical decisions.

- Management overhead: New management layers (promoted first engineers who are untrained managers) create coordination overhead. What previously required 2 engineers coordinating ad hoc now requires manager-to-manager coordination, meetings, written status updates, and documentation. Engineers spend more time in meetings and less time coding.

- Context switching: A growing organization fragments the company’s focus. At 8 engineers, there was one engineering team with one technical direction. At 25 engineers, there might be 3 teams with 3 different technical directions, 3 different priorities, and constant debates about resource allocation.

The net result: company hires 200% more engineers but achieves 30-50% less shipping velocity.

For a company dependent on product iteration speed to outcompete well-funded competitors, this velocity decline can be existential. The company that shipped 4 features per quarter at Series A is shipping 1-2 per quarter at Series B. Competitors who hired thoughtfully and scaled discipline with scale are shipping 5-6 features per quarter. Within 12-18 months, the company that had product advantage loses it.

Turnover Acceleration: The Retention Cliff

The most visible consequence of poor hiring and management practices: turnover accelerates after 18-24 months.

In a healthy growth-stage company:

- Year 1 turnover: 5-8% (normal churn from bad fits)

- Year 2 turnover: 5-8% (company has stabilized, good people stay)

- Year 3+ turnover: 8-12% (some people want larger companies or different challenges; normal for growth stage)

In a company with talent dysfunction:

- Year 1 turnover: 10-12% (initial hiring hasn’t separated good from bad fits yet)

- Year 2 turnover: 18-22% (people who realize the management environment is dysfunctional, people who got passed over for promotions, people who see better opportunities elsewhere)

- Year 3+ turnover: 25-35% (organizational antibodies rejecting people who don’t fit deteriorating culture, people who built the company moving to less chaotic environments)

By Year 3, the company is replacing 25-35% of its engineering team annually—the equivalent of completely replacing the team every 2.8-4 years.

This turnover has cascading financial consequences:

- Hiring and recruiting costs: Each replacement hire requires 3-4 months of recruiting, interviewing, offer negotiation. For a company with 40 engineers replacing 12 annually, this represents 1.5-2 FTE devoted to recruitment—an opportunity cost of $180-250K annually.

- Onboarding and productivity loss: Each departing engineer represents loss of institutional knowledge and context. Each new engineer requires 20-30% onboarding attention from existing team. The productivity tax compounds with high turnover.

- Knowledge loss: When senior engineers leave, particularly those who’ve been at the company for 3+ years, the company loses institutional knowledge that’s difficult to replace. Some of this knowledge can be documented, but much of it is procedural understanding that only manifests through observation and mentorship.

- Morale deterioration: High turnover creates organizational instability. People who might have stayed become concerned about company stability (“If good engineers are leaving, should I be looking too?”). People who know they’ll have fewer colleagues in 12 months become less invested in building systems meant to last. Institutional cynicism sets in: “Why invest in infrastructure when we’re shipping fast and shedding people constantly?”

For a company with $20M ARR and 40 engineers, 25-30% annual turnover costs approximately $2-3M in direct recruiting and onboarding costs, plus an additional $3-5M in productivity loss. Over 3 years, this represents $15-24M in cumulative value destruction—equivalent to 40-75% of Series B funding in many cases.

Talent Stratification: The Widening Skill Gap

As companies grow and hiring standards deteriorate, they develop stratified talent pools: a cohort of early employees (pre-Series B) with high capability and alignment, and a larger cohort of growth-stage hires with more variable capability.

This creates skill mismatch and organizational dysfunction:

- Limited mentorship availability: The 8 high-capability early engineers are swamped answering questions from 20+ growth-stage hires. Mentorship that should be deliberate and structured becomes reactive and fragmented. Junior engineers aren’t systematically developed; they’re pointed at problems and expected to figure out solutions.

- Architecture divergence: Early engineers who understood architectural principles build coherent systems. Growth-stage hires who didn’t receive deep architecture context build systems that don’t fit architectural patterns. The company’s codebase gradually becomes incoherent—different modules use different patterns, integration points are ad hoc, and new engineers struggle to understand existing systems.

- Promotion stagnation: Early employees expect promotion opportunities as the company grows. If those promotions go to equally capable growth-stage hires, early employees become frustrated. If promotions are reserved for early employees despite growth-stage hires’ capabilities, resentment builds. The company is forced to choose between disappointing early employees or creating perceived unfairness in promotion standards.

- Attrition of high performers: High-capability engineers recognize that company culture has deteriorated and that their opportunities to impact company trajectory have diminished as organization size and bureaucratic processes increase. They leave for opportunities where they can make more impact—either joining better-managed growth-stage companies, starting their own ventures, or joining later-stage companies with resources but smaller individual impact.

The net effect: the cohort of engineers who had capability to drive company trajectory is reduced, and the company develops a larger base of individual contributors who are competent but not high-impact.

Customer Impact: The Product Quality and Reliability Tax

Poor hiring and insufficient onboarding don’t remain internal problems. They manifest in customer-facing product quality and reliability degradation.

When new engineers aren’t thoroughly trained on architecture and build systems without understanding existing patterns, the result is accumulating technical debt. The company ships faster in the short term (new code gets written faster) but slower long-term (more debt requires remediation). Within 12-18 months, the company finds itself unable to ship new features because it’s spending 50-60% of engineering capacity remediating technical debt.

More immediately, insufficient onboarding and QA discipline result in more production bugs. New engineers don’t understand system edge cases, haven’t participated in post-mortems for past failures, and make mistakes that experienced engineers would avoid. Within 18 months of aggressive hiring, many growth-stage companies experience a 30-50% increase in P0/P1 bugs in production.

For SaaS companies, this translates to:

- Increased customer escalations and support costs

- Higher churn among customers who encounter product reliability issues

- Reduced ability to close enterprise deals because customers lose confidence in reliability

- Revenue impact equivalent to 5-15% customer churn or 3-6 month extension in sales cycle

For a company with $20M ARR and 40% gross margins, a 10% incremental churn attributable to product reliability issues represents $2M in annual revenue impact.

Strategic Capability Loss: Inability to Execute Complex Initiatives

Complex technical initiatives (data platform buildout, infrastructure modernization, security hardening, system rewrites) require sustained focus from a cohesive technical team. They take 6-12 months and require engineers who understand company context, can make architectural decisions without requiring constant review, and can operate with minimal supervision.

Companies with high turnover and poorly integrated new hires can’t execute complex initiatives. These companies are stuck executing small feature work (shipping new customer-facing features monthly) but unable to invest in platform work that would improve long-term velocity, security, or reliability.

This creates a strategic trap: the company that can’t invest in infrastructure becomes progressively slower and less reliable, which creates more pressure to hire, which creates more turnover, which increases infrastructure deficit.

Within 3-5 years, this company faces a choice: invest 18-24 months in major infrastructure rebuilds (foregoing feature development) or be acquired for a discount to acquirers who can do the infrastructure work post-acquisition.

Why Talent Dysfunction Persists: The Structural Reasons Growth-Stage Companies Don’t Fix Hiring

Given the obvious costs of poor hiring and high turnover, why do growth-stage companies persist in these patterns? Several structural reasons:

Pressure for Speed Overrides Standards

In growth-stage companies, the founder’s mandate is clear: “Ship faster than competitors.” This creates a cultural imprint where speed is elevated above all other considerations.

When the CTO recommends hiring a candidate who isn’t quite right but could be productive in 6-8 weeks versus waiting 6 more weeks for an ideal candidate, the pressure for speed wins. The startup that hires the “pretty good” candidate ships new features 4 weeks earlier than the startup that waited for the perfect candidate. In the near term, this speed creates competitive advantage. Over 2-3 years, the speed advantage evaporates as technical debt and team dysfunction accumulate, but the decision was made with short-term incentives and visibility.

Venture Capital Timing and Pressure

Growth-stage companies operate under venture capital timelines. If a Series B investor gives the company 18 months to reach specific revenue or user targets, this creates urgency that overrides hiring discipline. The CTO is told: “I need 10 engineers hired in the next 8 weeks so we can execute this roadmap.” Disagreeing with the timeline is seen as unambitious.

Additionally, many venture investors focus on revenue and user growth metrics, not on engineering culture or team quality metrics. A CEO who reports “Growing 20% month-over-month” receives more investor enthusiasm than a CEO who reports “Growing 15% month-over-month but with a 5% engineering turnover rate and carefully planned hiring pipeline.” Investor incentives don’t align with long-term team health.

Founder Uncertainty About Scaling Management

Many growth-stage founders have been excellent individual contributors or have led small teams but have never scaled a company beyond 30-40 people. They’re uncertain about how to adapt their leadership style for larger teams. They’re uncomfortable with formal processes like structured hiring, onboarding curricula, or management training.

This uncertainty creates a pattern: rather than investing in systematic hiring and management discipline, founders default to “hire smart people and let them figure it out.” This worked at 10 people (smart people can figure out almost anything in a small team). It doesn’t work at 40 people (smart people still need structure and mentorship to perform well in larger organizations).

Lack of Visible Accountability for Talent Quality

Hiring decisions have long feedback loops. When a company hires 30 engineers across 12 months, the bad decisions don’t fully manifest until 18-24 months later. By then, the person who made the hiring decision may have been promoted, changed roles, or departed. There’s no tight accountability for hiring quality.

This creates a risk-shifting dynamic: the CTO is measured on “hire 25 engineers by Q3,” not on “hire 25 engineers who are >80% effective by Month 18.” Achieving the hiring target is rewarded; the downstream consequences of poor hiring aren’t connected to the decision-maker.

The Framework: How to Acquire and Retain High-Caliber Talent at Scale

Growth-stage companies that systematically address talent acquisition and retention challenges transform talent from a competitive vulnerability into a strategic advantage. Several patterns distinguish successful growth-stage companies from those that experience the dysfunction described above.

Principle 1: Hiring Standards Are Non-Negotiable

The highest-performing growth-stage companies treat hiring standards as immovable constraints, not variables to adjust based on timelines.

This means:

- CTO ownership of hiring standards and authority to say “no” to business pressure to lower standards

- Executive leadership acknowledges that timeline negotiation happens, but hiring quality standards don’t

- Structured evaluation process: technical assessment + culture fit assessment + skill alignment + reference checks

- Each hire goes through 4-5 structured interactions (phone screen, technical interview, culture interview, reference checks, final interview with executive)

- Explicit criteria for each hiring level (Senior engineer requires: 5+ years experience, demonstrated mentorship, architectural thinking; Mid-level engineer requires: 2-3 years experience, technical depth in relevant domains, learning orientation)

- Regular review of hiring decisions: 3, 6, 12 month retrospective on each cohort to identify systematic issues

Principle 2: Onboarding is Structured, Deliberate, and Resourced

High-performing companies recognize that onboarding isn’t access provisioning; it’s capability development.

Structured onboarding includes:

- Week 1: Company strategy, product roadmap, business model, customer context (manager owns this)

- Week 1-2: Architecture deep dive, technology stack overview, data model explanation, deployment process walkthrough (CTO or Lead Architect owns this—minimum 20 hours)

- Week 2-4: Codebase orientation, code reading, making first contributions with high-touch code review feedback (assigned mentor owns this—minimum 15 hours weekly)

- Week 2-6: Key relationships (meet every team, understand how engineering connects to other functions, participate in cross-functional meetings)

- Month 2: First substantial project (something non-critical that provides real contribution, not a toy project)

- Month 3: Retrospective on onboarding (what was missing? what was confusing? what would have accelerated capability development?)

This represents 60-80 hours of structured onboarding across first month from existing team. For a company adding 5 engineers in a quarter, this represents 1 FTE of onboarding investment. For a company adding 20 engineers in a year, this represents 4-5 FTE of dedicated onboarding focus.

This seems expensive. Over a 3-year period, this investment prevents 20-30% of new hires being ineffective, delivering $500K-$2M in value through retained productive employees.

Principle 3: Management Capabilities are Developed Systematically

High-performing companies don’t assume technical excellence correlates with management capability. Instead, they systematically develop people into management roles.

This includes:

- Assessment before promotion: Before promoting an individual contributor into a management role, assess whether they have management orientation (do they enjoy developing people? are they comfortable with difficult conversations? can they think strategically beyond their individual work?)

- Training before management transition: Before someone becomes a manager, provide 40-50 hours of management training covering: delegation, feedback delivery, career development, goal-setting, making strategic decisions, managing conflict

- Mentorship during transition: New managers should have a mentor (ideally CTO or experienced VP) who they meet with weekly. Mentorship focuses on: specific team challenges, making management decisions, people development, role modeling

- Clear expectations: New managers should understand what success looks like (productivity of their team, retention of their team members, development of individual contributors, execution of strategic initiatives)

- Regular feedback: Quarterly feedback on management performance separate from engineer performance reviews

Principle 4: Technical Leadership Continuity Protects Institutional Knowledge

High-performing companies recognize that early technical leaders (CTO, first 3-5 engineers) have irreplaceable institutional knowledge.

Strategies for protecting this knowledge:

- Succession planning: When it becomes clear that a technical leader will eventually move on (founder transitioning to CEO only, engineer moving on from company), explicit succession planning begins. The successor is identified 12+ months before transition and spends time with the departing leader learning decision-making rationale and architectural history.

- Architecture documentation: Key architectural decisions are documented (why this tech stack? why this database approach? what were alternatives considered and why were they rejected?). This isn’t bureaucratic documentation; it’s strategic context.

- Knowledge transfer sessions: When senior engineers depart, structured sessions occur (1-2 days) where departing engineer walks through architecture, past decisions, and future recommendations with remaining technical team.

- Institutional memory preservation: The company explicitly maintains one person (usually the CTO, sometimes the VP of Engineering) who holds context about “why things are the way they are” and makes this person available to explain context to new hires.

Principle 5: Compensation and Career Growth Align with Retention

High-performing companies recognize that after 18-24 months, talented people either have clear career growth opportunities or will leave.

Strategies:

- Transparent career paths: Individual contributors understand the technical career progression (IC1 → IC2 → IC3 → Principal/Distinguished Engineer). They know what skills and impact are required for each level and can see where they’re tracking against progression.

- Intentional stretch assignments: People who’ve mastered their current role are given projects that develop next-level capabilities. This prevents stagnation and keeps high performers engaged.

- Compensation benchmarking: The company regularly reviews compensation against market benchmarks. After 18-24 months, people who’ve developed substantial impact should be compensated at or above market rates. If the company can’t afford to match market, it acknowledges this risk explicitly rather than hoping for loyalty.

- Career conversations: Quarterly 1-on-1s between managers and reports explicitly discuss career development. The company asks: “What are your career aspirations? What skills are you looking to develop? What opportunities would accelerate your growth?”

Principle 6: CTO/VP Engineering is Fractional Advisor During Early Scaling

Here’s where this connects to fractional CTO/CISO services.

The highest-impact intervention for growth-stage companies struggling with talent acquisition and retention is experienced fractional CTO/VP Engineering advisory during the first 24 months post-Series B.

Here’s why this is valuable:

- External perspective on hiring and management: A fractional CTO has seen 20-30 growth-stage companies go through scaling. They recognize the patterns that lead to effective vs. ineffective scaling. They can advise the founding CTO on:

- Hiring standards appropriate for the company’s stage

- Early warning signs that hiring is deteriorating (ratio of “pretty good” hires increasing, feedback from interviewers about candidate quality declining)

- Management structures that work at different company sizes

- Onboarding processes that scale

- Common mistakes that lead to dysfunctional scaling

- Active participation in hiring: Rather than just advising, an effective fractional CTO participates in senior hiring decisions. They conduct final technical interviews, assess cultural fit, provide gut-check on hiring decisions. Their presence elevates hiring standards because hiring managers know their decisions will be reviewed by someone with external perspective and experience.

- Management mentorship for first-time managers: A fractional CTO provides weekly or bi-weekly mentorship to newly promoted managers, helping them navigate the transition from individual contributor to manager. This prevents many of the common mistakes (micromanagement, lack of strategic perspective, poor hiring decisions) that derail new managers.

- Early warning system for team dysfunction: A fractional CTO regularly talks to engineers (skip-level meetings, informal conversations). They hear about issues before they become crises: management problems, team conflicts, burnout indicators, people considering departure. They surface these issues to leadership and help course-correct before they result in unexpected departures.

- Strategic input on technical direction: A fractional CTO helps the founding CTO think through architectural decisions, technology choices, and infrastructure investments with a longer-term view. This prevents some of the “smart people figuring it out” mistakes that accumulate into major technical debt.

- Institutional knowledge documentation: A fractional CTO works with founding technical leaders to document architectural history, why key decisions were made, and what alternatives were considered. This preserves context when people eventually depart.

For a growth-stage company investing $500K-$2M in hiring across 12-18 months post-Series B, a fractional CTO ($15K-$25K monthly engagement for 12-24 months) is extraordinarily high-ROI. They prevent 20-30% of hiring mistakes, reduce turnover by 10-15%, accelerate new manager development, and protect institutional knowledge.

Actionable Recommendations for Growth-Stage Companies

Based on current research and scaling experience, growth-stage CTOs and founders should:

-

Establish Hiring as an Operational Discipline in First 100 Days Post-Series B Rather than treating hiring as a continuous ad hoc process, establish it as a structured discipline:

- Define hiring standards explicitly (skill requirements, experience levels, cultural fit criteria)

- Design structured interview process (phone screen, technical interview, culture interview, reference calls, executive meeting)

- Assign hiring owner (usually CTO or VP Engineering) with authority to say no

- Track hiring metrics: candidate source, pass rates at each stage, offer acceptance rate, 6-month and 12-month performance of each cohort

- Monthly review of hiring cohorts to identify systematic issues

-

Build Onboarding Curriculum in Parallel With Hiring Before aggressive hiring begins, develop onboarding curriculum:

- Define what every new engineer needs to know in Week 1, Weeks 2-4, Month 2, Month 3

- Develop architecture walkthroughs, codebase documentation, company strategy overview

- Identify mentors who will be responsible for new hire capability development

- Allocate 60-80 hours of existing team time per new hire for onboarding

- Monthly review of onboarding effectiveness (are new hires independently productive by Month 3?)

-

Develop First-Time Managers Before Promotion Rather than promoting early employees into management and hoping they figure it out:

- Assess management orientation before promotion (do they want to develop people?)

- Provide 40+ hours of management training (delegation, feedback, career development, strategic thinking)

- Pair new managers with mentors (experienced VP or fractional CTO)

- Set clear performance expectations for new managers (team productivity, retention, individual development)

- Quarterly feedback on management performance

-

Engage Fractional CTO/VP Engineering as Hiring and Management Advisor For companies that haven’t had fractional CTO services before, this is the most impactful investment:

- 12-24 month engagement starting at Series B

- Active participation in senior hiring decisions

- Weekly mentorship for newly promoted managers

- Regular conversations with engineers (skip-level meetings)

- Documentation of architectural decisions and institutional knowledge

- Strategic input on technical direction and infrastructure investments

- Expected ROI: 15-25% reduction in bad hiring decisions, 10-15% reduction in turnover, 20-30% faster new manager development. For a company with $2M hiring budget and talent dysfunction, this translates to $300-500K in protected value, delivering 10-20x ROI on fractional CTO engagement.

-

Implement Transparent Career Paths and Compensation Benchmarking After 18 months, engineer retention correlates strongly with:

- Clear understanding of career progression

- Stretch assignments that develop next-level capabilities

- Compensation at or above market rates

- Regular career conversations with management

- Establish: career level definitions, compensation benchmarks by level, quarterly career development conversations, intentional stretch assignments for high performers.

-

Monitor Turnover and Team Health Metrics Beyond financial metrics, track:

- Monthly turnover rate (separate voluntary vs. involuntary)

- Turnover by tenure (is the company losing people at 18-24 months? This is a red flag)

- Engineering productivity (features shipped per engineer per quarter)

- New hire productivity at Month 3, Month 6, Month 12 (are they independent by Month 6?)

- 360-degree feedback on managers (are people happy with their managers?)

- Employee engagement surveys quarterly (are people planning to stay?)

These metrics provide early warning of talent dysfunction before it becomes critical.

Conclusion: Talent Acquisition as a Strategic Competitive Advantage

The 82% of growth-stage companies citing talent acquisition as their greatest challenge reflects a well-founded concern. Talent acquisition dysfunction directly impairs engineering velocity, generates technical debt, reduces product reliability, creates management dysfunction, and accelerates turnover that further degrades company performance.

Yet talent acquisition dysfunction is not inevitable. Growth-stage companies that systematically address it—through structured hiring, deliberate onboarding, management development, fractional CTO advisory, career path clarity, and compensation alignment—transform talent from a vulnerability into a competitive advantage.

For companies with integrated hiring discipline, effective onboarding, developed managers, and clear career paths, engineering velocity compounds. Complex technical initiatives get executed. Product reliability improves. Talented people choose to stay. For CTOs, founders, and operating partners responsible for engineering effectiveness and company trajectory, treating talent acquisition not as a perpetual crisis but as a strategic operational discipline is essential to competitive performance.

The companies that will dominate growth stage exits and Series C dynamics are those that built talent acquisition discipline and protected it even under pressure to scale faster. For the fractional CTO community, this is the highest-impact engagement opportunity: helping growth-stage companies scale their teams while maintaining the hiring standards, management discipline, and institutional knowledge preservation that enable sustained velocity and team health.