AI/ML Capability Assessment and Implementation Risk: The Hidden Dangers of "Fake AI" in PE Acquisitions

Why PE firms overpay for "Fake AI" and how to identify genuine capabilities versus marketing fiction in due diligence.

When a private equity firm acquires a software company positioned as an AI powerhouse, due diligence typically involves financial audits, customer interviews, and strategic fit analysis. What it often fails to involve is rigorous technical validation of whether the company’s AI capabilities are real, overmarketed, or entirely fabricated. This gap between acquisition claims and operational reality has become one of the most damaging blind spots in PE deal-making, resulting in portfolio companies built on false technological foundations, regulatory exposure, and destroyed value that only becomes apparent post-acquisition.

The evidence of this blind spot emerged dramatically in 2025 with the collapse of Builder.ai, a London-based startup once valued at $2.3 billion and backed by Microsoft, SoftBank, and Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund. For nine years, Builder.ai marketed itself as an AI-powered no-code development platform powered by an intelligent assistant called “Natasha” that could automate software development at scale. In reality, internal investigations revealed that approximately 700 human developers in India were manually writing code line-by-line based on customer requests, then repackaging it under the “AI-generated” label. The company inflated revenues by over 300%, engaged in “round-tripping” financial schemes with partner companies to artificially inflate sales, and eventually filed for bankruptcy after losing $77 million in seized assets. More importantly, customers who believed they were purchasing genuinely scalable AI automation discovered they were dependent on unsupported human-driven processes that couldn’t scale, leaving their products incomplete and their platforms fragile.

The Builder.ai case represents an extreme manifestation of a broader phenomenon now known as “AI washing”—the practice of exaggerating, falsifying, or deliberately misrepresenting AI capabilities to investors and customers. But beyond the theatrical fraud cases lie subtler versions of the same problem: companies that genuinely use machine learning but vastly overstate the sophistication of their models, companies that bolt AI onto traditional software and market it as AI-first platforms, and companies that rely on narrow AI applications while claiming general-purpose AI capabilities. The challenge for PE acquirers is that distinguishing genuine innovation from sophisticated deception requires specialized technical expertise that most acquisition teams lack, creating an asymmetry of information where sellers have every incentive to maximize perceived AI capabilities and buyers have insufficient tools to verify claims.

The consequences extend far beyond the Builder.ai debacle. PE-backed portfolio companies built on misrepresented AI capabilities face regulatory penalties, customer defection, competitive disadvantage, operational fragility, and the discovery of massive hidden integration costs. The Federal Trade Commission’s 2024 “Operation AI Comply” enforcement sweep resulted in five major enforcement actions against companies making false AI claims, with fines ranging from $193,000 to millions, combined with injunctions against continued marketing of deceptive AI products. Yet these represent only the prosecuted cases. Dozens of portfolio companies operate on false technological assumptions, creating value destruction that remains invisible until post-acquisition integration reveals that the platform everyone believed was AI-powered is actually held together by workarounds, manual processes, and technical debt. This article deconstructs the AI capability assessment problem in PE acquisitions, revealing what constitutes fake AI, why it passes traditional due diligence, how to distinguish genuine capabilities from marketing fiction, and what regulatory and operational risks emerge post-acquisition when the truth emerges.

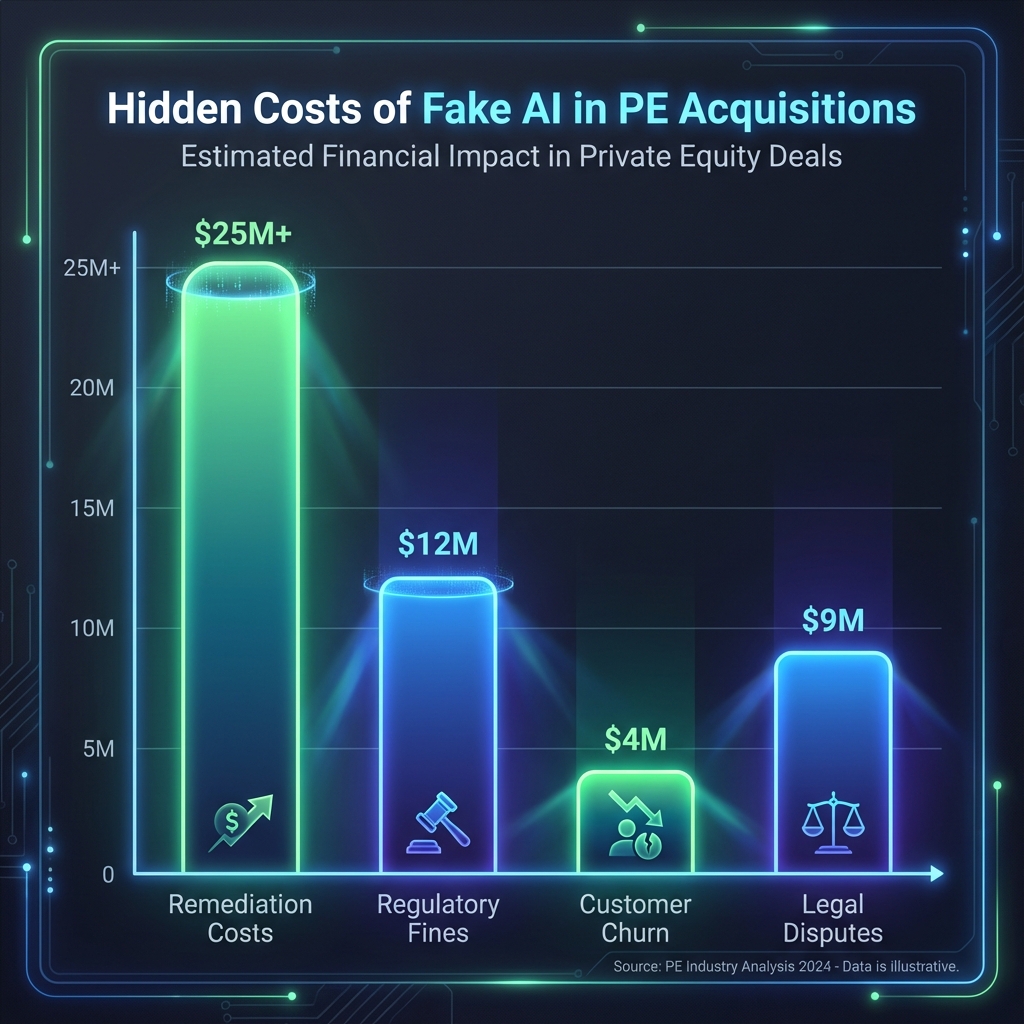

The True Cost of Misassessing AI Capabilities

Before examining how to detect fake AI, PE firms must understand the financial consequences of getting it wrong. The costs operate across multiple dimensions.

Post-Acquisition Discovery and Remediation Costs

When a PE firm acquires an AI-driven software company and subsequently discovers that the core technology is either non-functional or vastly overstated, the firm faces immediate remediation challenges. If the platform is customer-facing and customers are paying for AI capabilities, the firm must either rebuild the platform on genuine AI foundations (a multi-year, multi-million dollar undertaking) or communicate to customers that their purchased capabilities don’t exist as promised, triggering refunds, contract terminations, and litigation.

Consider the operational reality for a PE firm acquiring a “machine learning-powered” analytics platform marketed as delivering 95% accuracy in customer churn prediction. During post-acquisition technical audit, the firm discovers that 80% of the model’s accuracy comes from hard-coded business rules developed by engineers (not machine learning), and the actual machine learning model contributes minimal incremental accuracy. The company has been overselling ML capabilities while being fundamentally dependent on brittle business logic that breaks when customer data patterns shift even slightly. The firm now faces a choice: invest $5-15 million over 18-24 months to rebuild genuine machine learning infrastructure, or accept that the core value proposition is unsustainable and the platform cannot command premium pricing.

During the 2024-2025 period, organizations attempting AI implementations discovered this problem repeatedly. MIT research found that 95% of enterprise generative AI pilots fail to deliver measurable P&L impact, primarily due to integration, data, and governance gaps rather than model capability issues. More directly, 42% of companies scrapped most of their AI initiatives in 2024, with cumulative investments stranded in failed pilots and abandoned projects. For a portfolio company where AI represents the core value proposition, this discovery transforms a strategic asset into a liability.

Regulatory Penalties and Enforcement Risk

The FTC and SEC have made enforcement against deceptive AI claims an explicit priority. The FTC’s Operation AI Comply enforcement sweep brought action against companies making false claims about AI capabilities, with penalties including both monetary fines and ongoing advertising restrictions. DoNotPay, a company claiming to offer a “robot lawyer,” faced a $193,000 fine for making unsubstantiated claims about its AI chatbot’s ability to deliver legal advice and document generation. But the fine itself represents only a fraction of the actual damage—the company also faced mandatory customer notifications warning about service limitations, reputational destruction, and litigation from customers who purchased services based on false AI representations.

For a PE-backed portfolio company, regulatory enforcement creates cascading damage. First, the direct regulatory penalty (which can range from hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars depending on company size and violation severity). Second, mandatory remediation of all marketing materials and product claims, requiring legal and technical expertise to reposition the product truthfully. Third, customer notification obligations that effectively acknowledge to the market that the company made false claims, triggering customer churn and potential litigation. Fourth, the probability of derivative regulatory action—if the FTC or SEC is investigating one AI claim, regulators typically expand investigation to examine other product claims and statements.

The regulatory framework now explicitly targets AI washing. FTC guidance makes clear that companies making any of the following claims face enforcement action: exaggerating what AI systems can do, making claims without scientific support or applying only under limited conditions, making unfounded promises that AI does something better than non-AI alternatives or humans, failing to identify known likely risks associated with AI systems, and claiming products use AI when they do not. A PE-backed portfolio company that marketed a product with any of these claims now faces explicit regulatory liability.

Customer Churn and Revenue Impact

When customers discover that their purchased AI capabilities don’t exist or function far differently than promised, the outcome is customer defection. In B2B software, customer acquisition costs typically range from $30,000 to $300,000 depending on deal size and sales cycle. When a customer churns due to false AI capability claims, the company loses not only the current contract value but also the acquisition cost investment, the implementation and support costs incurred, and the Net Lifetime Value of the relationship. For a SaaS company with 85% net retention rate that suddenly faces 30-40% churn due to AI capability issues, revenue can decline by 15-25% within 12 months.

The Builder.ai case illustrated this damage. Customers who purchased the platform believing they were accessing genuinely scalable AI automation suddenly discovered their projects depended on manual human development. They faced incomplete deliverables, unsupported codebases, and platforms that couldn’t scale independently of the vendor’s manual labor. The discovery triggered immediate customer defection and lawsuit preparation. For the customers (many of them early-stage companies themselves), the damage was existential—they had prioritized accessing “AI automation” and deprioritized building alternative solutions, leaving them stranded when the platform proved false.

Talent Retention and Team Capability Loss

When a PE firm acquires an “AI-first” company and subsequently discovers the AI capabilities are overstated, the engineering team typically experiences organizational dysfunction. Teams hired specifically to build genuine AI systems suddenly discover they’re maintaining manual workarounds instead of evolving machine learning models. Senior ML engineers recognize the situation as technically unsustainable and begin interviewing elsewhere. The company loses its most capable technical talent precisely when it needs maximum capability to fix the underlying problems.

This creates a compounding deterioration. A company built on false AI foundations is also typically built on engineering debt (because the human-driven alternative to real ML often involves quick-and-dirty solutions). With talented engineers departing and the company’s technical challenge becoming more visible, the firm experiences cascading talent loss exactly when it needs to rebuild credibility through genuine technical excellence.

Strategic Value Destruction

Beyond direct costs, misassessed AI capabilities destroy strategic value by creating an impossible position for exit. When a PE firm attempts to exit a portfolio company whose AI capabilities proved overstated during the holding period, buyers conduct their own technical due diligence and quickly identify the capability gap. Buyers naturally apply significant discounts to valuations for companies with compromised AI positioning. If the company was acquired at 6x revenue based on AI-powered competitive advantage, and exit buyers discover the AI is largely fictitious, the company might exit at 3-4x revenue, destroying $50+ million in value on a $100 million business.

Additionally, if the buyer discovers that the PE firm concealed or failed to identify the AI capability gap during acquisition, the buyer may seek indemnification for damages, triggering post-closing disputes that consume months of management time and legal resources.

How “Fake AI” Passes Traditional Due Diligence

The persistence of AI washing in PE acquisitions reveals critical gaps in how traditional due diligence frameworks assess technology claims. Most PE firms’ due diligence processes are designed for financial and commercial validation, not technical verification of complex technical claims.

The Information Asymmetry Problem

Sellers of AI companies have every incentive to maximize perceived AI capabilities. Founders may genuinely believe their overstated claims (some are deluded by their own marketing), or they may deliberately mislead knowing that due diligence timelines compress incentives toward deal closure. Buyers, by contrast, operate under time pressure and face potential deal failure if they delay closure with technical challenges. When a seller says “Our AI model achieves 95% accuracy in customer churn prediction” and buyer’s technical team raises questions about model architecture or training data, the conversation typically defaults to seller reassurance rather than independent verification.

This asymmetry compounds because the buyer team often lacks the specialized expertise to assess AI claims credibly. A partner from a consulting background or a VP Product can ask reasonable-sounding questions about model performance, but lacks the depth to distinguish between genuine machine learning and sophisticated marketing. When a seller describes model architecture using technical terminology (convolutional neural networks, ensemble methods, federated learning), a non-specialist buyer team often defaults to assuming competence and moving forward with the deal.

The Charisma of AI Marketing

AI has become sufficiently fashionable in Silicon Valley that companies marketing themselves as “AI-first” or “powered by machine learning” benefit from perceived sophistication and cutting-edge positioning. Investors have been conditioned to believe that AI represents defensible competitive advantage, that AI-powered businesses command premium valuations, and that AI acquisitions represent strategic necessity in an AI-dominated future. This marketing environment creates psychological bias toward accepting AI capability claims at face value.

Companies exploit this bias deliberately. Builder.ai positioned founder Sachin Dev Duggal as “chief wizard,” appeared on podcasts as an AI industry expert, and communicated using the language of AI innovation. This branding created an aura of technical sophistication that disarmed skepticism. When customers or investors encountered unexplained operational issues or questioned architecture details, the branding provided protective cover—surely such a prominent AI thought leader wouldn’t be running a manual labor farm, they reasoned.

The Opacity of Machine Learning Systems

Machine learning systems are inherently difficult to audit from the outside. A well-designed model can produce accurate predictions using methods that are genuinely intelligent, or can achieve similar accuracy through much simpler mechanisms that look intelligent to end-users. The “black box” nature of machine learning means that even trained data scientists can have difficulty fully understanding how a model generates its predictions without access to training data, feature engineering logic, and model architecture details.

This opacity creates perfect conditions for deception. A company can build a product that delivers accurate results using hard-coded business rules, wrap it in a machine learning API, and claim to be running genuine AI. End-users see accurate outputs and assume machine learning is responsible, when in reality they’re using static logic. The only way to distinguish the difference is through detailed technical audit requiring access to training data, model code, inference logs, and performance metrics across different input types.

The Compression of Technical Due Diligence

PE acquisitions operate on compressed timelines. From initial contact to deal close, firms typically allocate 60-120 days. During this period, the team must conduct financial audit, legal review, customer interviews, and technical assessment—compressed into a timeline that normally would take 6 months or more. This time compression means technical due diligence receives fractional attention.

Technical due diligence of an AI company requires: understanding the model architecture and algorithm, accessing training data to verify data quality and completeness, testing model performance across multiple scenarios and data types, reviewing model monitoring and retraining processes, assessing deployment infrastructure and scalability, and understanding the team’s machine learning expertise and governance. Each of these elements requires 2-4 weeks of detailed work. In a compressed 120-day timeline, technical due diligence of this depth is frequently deprioritized in favor of financial and legal closure mechanics.

The Lack of Standardized AI Validation Frameworks

For financial due diligence, PE firms employ standardized frameworks: revenue validation, customer concentration analysis, churn rate verification, margin trend analysis. These frameworks exist because financial data is standardized and can be independently verified.

For AI capability assessment, no equivalent standardized framework exists. Different companies use different modeling approaches, different datasets, different performance metrics, and different deployment infrastructures. A buyer assessing an AI company is often examining novel technology using ad-hoc assessment criteria. This lack of standardization means validation is slower, more expensive, and more easily manipulated than financial audit.

Categories of Fake AI: From Egregious Fraud to Subtle Overstatement

Not all AI washing is equally egregious. Understanding the spectrum of fake AI helps PE firms identify varying degrees of misrepresentation.

Category 1: Explicit Human Labor Misrepresented as Automation

At the extreme end of the spectrum, companies simply claim to be operating AI automation while actually employing human labor. Builder.ai represents this category—700 developers manually writing code while the company marketed “Natasha” as intelligent automation. The lie is explicit and total: customers purchasing what they believed was machine-learning-driven automation were actually accessing expensive human labor at a price point engineered to appear competitive with genuine automation.

The detection mechanism is straightforward but requires investigation: Does the company’s cost structure align with claimed automation levels? If a company claims to deliver software development “6x faster and 70% cheaper” through AI, what are the actual operating costs? If the company’s largest operating expense line is direct labor (software developers), that represents a red flag. Does the company scale linearly with volume (characteristic of manual labor) or scale sub-linearly with volume (characteristic of automation)?

Category 2: Hard-Coded Business Rules Marketed as Machine Learning

A more common form of fake AI involves implementing product logic using hard-coded business rules, then marketing the result as “machine learning-powered.” For example, a loan underwriting company might implement a rule: “Approve loans for applicants with credit score > 750 and debt-to-income < 40%, and flag all others for manual review.” This rule delivers accurate predictions in the training population but is fragile—when credit scoring methodologies change or borrower populations shift, the rule stops working. The company can market this as “AI-driven underwriting” and customers will experience accurate results in the short term, but the system is fundamentally not adaptive to new data.

The detection mechanism: Demand documentation of model architecture, training data, and retraining processes. If the company cannot produce training code, cannot explain how features are engineered, or resists providing model performance metrics across different time periods or borrower segments, that suggests the system relies on hard-coded rules rather than genuine machine learning. Ask specifically: “What happens to model performance if input data distributions change?” If the answer is vague or evasive, the system likely isn’t genuinely learning.

Category 3: Narrow Task Models Marketed as General AI

A company might build a genuinely useful machine learning model that solves a specific narrow problem—for example, predicting customer churn within a specific industry vertical with specific data types. The model works well for the narrow task it was trained on but fails dramatically when applied to different customer segments, different data types, or different prediction tasks. The company markets the model as “AI-powered” or “powered by advanced machine learning” without specifying the narrow domain of application, implying broader generalizability than exists.

This represents a more subtle form of deception because the AI is genuine—but scope-limited. Detection requires understanding the model’s domain specificity: Does the model work across industries or only within narrow customer segments? Does model performance degrade when applied to new geographies, new time periods, or new data distributions? Ask about out-of-sample testing: “Have you validated model performance on customer data that the model was never trained on?”

Category 4: Third-Party Models Rebadged as Proprietary AI

Some companies purchase commercial machine learning platforms (like cloud-based AI services from AWS, Google, or Azure) or open-source models, integrate them into products, and market the result as proprietary AI innovation. There’s nothing inherently deceptive about using existing models—many successful companies do so. The deception occurs when companies claim proprietary innovation they don’t possess or overstate their differentiation.

Detection requires asking: “What components of your AI system are proprietary versus leveraging third-party platforms?” If the core machine learning is powered by OpenAI’s GPT models, AWS ML services, or other commercial platforms, that’s fine, but should be disclosed and properly scoped. If the company claims proprietary breakthroughs in model architecture or training but actually uses standard commercial services, that’s misrepresentation.

Category 5: Minimal Machine Learning Augmentation of Traditional Software

This category represents the most common and subtle form of AI washing: companies that add a small machine learning component to traditional software and market the entire product as “AI-powered.” For example, a traditional CRM system might add machine learning to predict which leads are likely to convert, implement that model, then rebrand the product as an “AI-powered sales platform.” The prediction model might be genuinely useful, but represents perhaps 5% of platform functionality. Marketing the product as “AI-powered” implies AI is central to the platform and represents its primary differentiation, when in reality AI is a peripheral enhancement to traditional software.

The detection mechanism: Demand specificity about what AI does versus what traditional software does. “What percentage of user-facing functionality depends on machine learning versus traditional logic?” “What would the product deliver without the ML component?” “How much of the competitive advantage comes from AI versus other factors?” If the company struggles to articulate clear boundaries between AI and non-AI functionality, the AI is likely peripheral to the core value proposition and being oversold.

Technical Red Flags: What Due Diligence Should Investigate

PE firms can implement specific technical investigations during due diligence to identify likely AI washing before acquisition closes. These investigations require specialized expertise but are far less expensive than discovering problems post-acquisition.

Red Flag 1: Inability to Produce Clean Training Data and Methodology Documentation

Legitimate machine learning systems are built on documented training processes. Companies should be able to produce: training data description (size, sources, collection methodology), labeling process and accuracy verification, feature engineering logic and documentation, model architecture and algorithm selection rationale, hyperparameter tuning process and results, and cross-validation procedures and results. If a company cannot or will not produce this documentation, it suggests no rigorous machine learning process exists.

Ask specifically: “Can you show me your training data?” If the answer is “It’s proprietary and we can’t share it,” dig deeper. Proprietary is fine, but the company should still describe it in sufficient detail for auditors to understand data quality and representativeness. If the company provides training data but it appears suspiciously small (1,000 samples for a model claimed to power mission-critical customer decision-making), that’s a red flag. If the company provides data but refuses access to labeling methodology, model code, or performance metrics, that’s also a red flag.

Red Flag 2: Model Performance Claims Without Context

Deceptive companies frequently make performance claims like “95% accuracy” without providing context about what accuracy means, what the baseline is, or how performance varies across different input types. A company might report “95% accuracy” on a balanced dataset where randomly guessing would achieve 50% accuracy, making 95% sound impressive. On an imbalanced dataset where the base rate outcome occurs 95% of the time, “95% accuracy” is worse than doing nothing.

Request: “Show me the confusion matrix, precision, recall, F1 score, and ROC curve for your model, across different customer segments and time periods.” If the company provides only aggregate accuracy numbers, demand specificity. If model performance varies dramatically across different customer segments or time periods, that suggests the model isn’t genuinely learning generalizable patterns but is overfit to specific data subsets.

Red Flag 3: Scaling Claims Without Infrastructure Evidence

Companies often claim their AI systems can “scale infinitely” or “handle massive data volumes” without evidence of infrastructure designed to support claims. A company claiming their model processes “petabytes of data daily” through “advanced distributed architecture” should be able to describe their infrastructure (Kubernetes clusters, distributed training frameworks, data pipeline architecture). If they provide vague answers about cloud infrastructure without specifics, they may not actually be running genuine scaled AI operations.

Ask: “What tools do you use for model serving? How do you handle model inference at scale? What’s your p99 latency for predictions?” If they describe infrastructure using buzzwords (cloud, distributed, real-time) without technical specificity, dig deeper. If you can ask for architecture diagrams and they can’t provide them, that’s suspicious.

Red Flag 4: Model Instability and Retraining Necessity

Ask about model stability: “How often do you retrain your models and why?” Genuine machine learning systems require periodic retraining because model performance degrades as the underlying data distribution shifts. If a company claims its models require no retraining or updates, that suggests the system uses hard-coded rules rather than machine learning (because hard-coded rules don’t degrade as distributions shift, but also don’t adapt to new patterns).

Conversely, if a company reports needing to retrain models daily or weekly, that’s suspicious—high-quality machine learning systems typically maintain consistent performance for weeks or months before retraining becomes necessary. Very frequent retraining suggests model instability caused by poor feature engineering, inadequate training data, or overfitting to specific data subsets.

Red Flag 5: Lack of Model Monitoring and Governance

Legitimate machine learning operations include continuous monitoring of model performance in production. Companies should track: model accuracy over time, feature drift (changes in input data distributions), prediction drift (changes in output distributions), and performance differences across different customer segments or demographics. If a company cannot describe its model monitoring process, that suggests models are deployed without rigorous operational governance.

Ask: “What metrics do you monitor for your production models? How do you detect when model performance degrades? What’s your procedure for retraining or rolling back models?” If they describe vague processes or manual checks, that’s a red flag. Legitimate ML operations use automated monitoring frameworks to continuously assess model health.

Red Flag 6: Customer Complaints About Model Accuracy or Unusual Behavior

During customer interviews, specifically ask about model behavior and consistency. “Do model predictions seem to behave consistently?” “Have you experienced situations where predictions seem illogical?” “Does model accuracy seem to vary depending on input characteristics?” If multiple customers report inconsistent behavior, poor accuracy on edge cases, or predictions that don’t make logical sense, that suggests the underlying system isn’t genuinely learning but is using hard-coded rules or superficial pattern matching.

Regulatory Risks: What Emerges Post-Acquisition

PE firms that fail to identify fake AI during due diligence face specific regulatory risks once the acquisition closes.

FTC Enforcement Under Operation AI Comply

The FTC has made enforcement against deceptive AI claims a top priority. Under Operation AI Comply, the agency has brought enforcement actions against companies claiming false AI capabilities. The legal standard is straightforward: companies cannot make claims about AI capabilities that are false, misleading, or lack scientific substantiation. The FTC’s approach is aggressive—fines for identified violations have been substantial, and the agency requires ongoing compliance monitoring and customer notification.

For a PE firm that acquired an AI company based on false capability claims, the firm now bears responsibility as the company’s owner. The FTC can impose penalties against both the company and, in egregious cases, the PE firm itself for allowing deceptive practices to continue. The compliance burden is also significant—companies facing FTC enforcement must implement comprehensive monitoring of all marketing claims, obtain independent verification before making any AI-related claims, and maintain documentation supporting all claims about product capabilities.

SEC Enforcement Against Misrepresentation

The SEC has also prioritized enforcement against misleading claims about AI capabilities, particularly in public company contexts or where companies have raised capital based on AI claims. If a portfolio company is ultimately sold to a public acquirer or taken public, the acquirer or public market will investigate whether AI claims were false or misleading at the time of acquisition. If they were, and the PE firm failed to disclose the misrepresentation in acquisition documentation, the firm faces potential SEC investigation and enforcement action.

State Attorney General Enforcement

Multiple state attorneys general have launched investigations into AI deception and false claims. California, Texas, Massachusetts, and other states have explicitly warned companies that existing consumer protection laws prohibit false AI claims. For companies selling to consumers (even B2B where decision-makers are individuals), state AG enforcement represents a meaningful risk.

Customer Litigation

Customers who purchased AI capabilities believing they were genuine have standing to sue for breach of contract, misrepresentation, and damages. If customers relied on AI capabilities in making strategic business decisions (deploying capital, deprioritizing alternative solutions, making hiring decisions), and the AI proved false, customers can claim damages. In aggregate, customer litigation against an AI company with hundreds or thousands of customers can easily reach $10-50 million or more across multiple suits.

Indemnification Disputes With Seller

If the PE firm’s acquisition agreement included representations and warranties from the seller (standard in PE deals), the firm can potentially seek indemnification for damages resulting from false AI claims. However, indemnification typically has caps, time limits, and requires proof that the seller knowingly misrepresented capabilities. Disputes over indemnification consume significant legal and management resources while providing uncertain recovery.

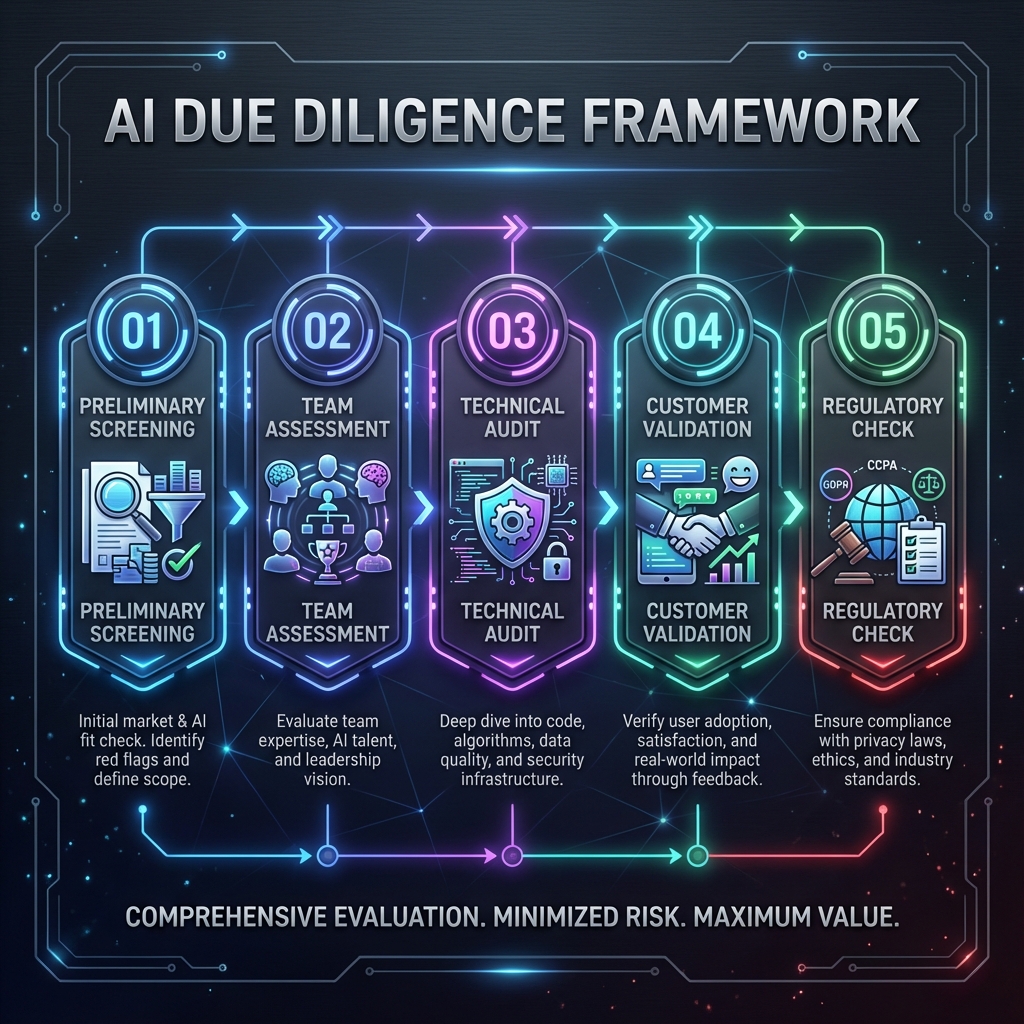

Due Diligence Framework: How to Assess AI Capabilities Credibly

PE firms seeking to avoid AI washing should implement a rigorous assessment framework during due diligence.

Phase 1: Preliminary Screening (Weeks 1-2)

Begin with targeted questions designed to identify immediate red flags. Request the following documentation: machine learning model inventory and descriptions, model performance metrics and historical tracking, model training and retraining procedures and schedules, model monitoring and governance procedures, customer feedback on model behavior and consistency, third-party integrations and dependencies.

Companies that cannot produce this documentation should be deprioritized as acquisition targets. The documentation doesn’t need to be perfect, but its absence suggests inadequate ML rigor.

Phase 2: Technical Team Assessment (Weeks 2-4)

Engage specialized ML/AI technical advisors to evaluate the company’s machine learning team and infrastructure. Key questions: What machine learning frameworks and tools do the team use? How many data scientists and ML engineers are on staff? What’s their experience building and deploying ML systems? Are they publishing research or contributing to open-source ML projects? Have they built ML infrastructure (training pipelines, model serving, monitoring)?

The quality of the technical team is a strong proxy for AI credibility. Companies with genuine ML expertise will have team members who can articulate model architecture, explain training procedures, discuss performance metrics, and defend technical decisions. Teams assembled to support fake AI will struggle with these conversations.

Phase 3: Detailed Technical Due Diligence (Weeks 4-8)

Conduct hands-on technical audit of the AI systems. This requires the engagement of specialized advisors (data scientists, ML engineers, AI researchers) and typically involves: accessing source code and model artifacts, understanding data pipelines and training procedures, running independent validation tests on model performance, stress-testing models on edge cases and unusual data, assessing model interpretability and explainability, reviewing model deployment infrastructure, assessing monitoring and governance procedures.

This phase is expensive (typically $50,000-$150,000 in advisor costs) but far cheaper than discovering post-acquisition that AI capabilities are false.

Phase 4: Customer Reference Validation (Weeks 3-8)

During customer interviews, ask detailed questions about model behavior: How consistently do predictions behave? Have you experienced situations where predictions seem inaccurate or illogical? Does model performance vary depending on input characteristics? Have model results required manual intervention or correction? Do you rely on the AI for mission-critical decisions or is it supplementary?

Multiple customers reporting similar concerns about model consistency or accuracy represent a red flag. Customer comfort with AI system reliability is a strong signal of whether the system is genuinely intelligent or is achieving results through other mechanisms.

Phase 5: Regulatory and Compliance Assessment (Weeks 1-8)

Evaluate what compliance obligations the AI system creates. If the AI makes decisions affecting consumers (hiring, lending, insurance, medical), what regulatory requirements apply? Have any regulatory investigations or complaints been filed against the company? Are the AI systems compliant with emerging AI regulations (EU AI Act, state-level AI regulations)? Have audit trails and explainability been implemented to satisfy regulatory requirements?

Companies with unresolved regulatory concerns around AI represent higher risk and should carry explicit regulatory risk premiums in valuation or require indemnification from the seller.

Post-Acquisition Validation and Remediation

If a PE firm acquires a company and subsequently discovers that AI capabilities were misrepresented or overstated, specific remediation steps minimize damage.

Immediate Assessment and Scoping

Engage independent technical experts to conduct rapid assessment of the gap between claimed and actual AI capabilities. Scope the magnitude of the problem: Is the AI completely fake (all human labor), or is it partially real with significant overstatement? What percentage of customer value depends on the false AI claims? What’s the technical cost to fix the system to meet original claims?

This assessment typically takes 2-4 weeks and costs $50,000-$150,000 but provides clarity on the scale of the problem.

Customer Communication and Damage Control

Communicate proactively with customers before they discover the issue independently. The communication should acknowledge the situation (without admitting liability), explain remediation efforts underway, and provide timeline for resolution. Transparent communication manages customer expectations and significantly reduces churn compared to reactive communication after customers discover the issue independently.

In parallel, ensure legal and compliance teams are engaged because customer communication creates written evidence that regulators may later review. Coordinate all customer communications with legal counsel.

Remediation Planning

Based on the technical assessment, develop a remediation roadmap addressing whether to:

- Rebuild genuine AI systems to meet original claims (most expensive but preserves strategic positioning)

- Pivot product positioning to focus on other value drivers and de-emphasize AI (less expensive but requires repositioning and customer expectations management)

- Divest the asset and cut losses (most direct approach but takes significant value destruction)

The optimal approach depends on the specific situation, but should be decided quickly (within 4-8 weeks post-discovery) to minimize ongoing value destruction.

Strategic Recommendations for PE Firms

Based on research on AI washing and its consequences, PE firms managing technology acquisitions should:

- During investment screening: Deprioritize companies that cannot clearly articulate their AI/ML value proposition or produce documentation of model performance, training procedures, and monitoring systems. The presence of specialized ML talent (PhDs in machine learning, published researchers, prior ML startup experience) is a strong indicator of genuine AI capability.

- During due diligence: Allocate specific budget and timeline for technical AI due diligence. Don’t attempt to compress this assessment into 2-3 weeks. Engage specialized advisors with machine learning expertise, not just software engineers. Request and independently audit model performance metrics, training data, and deployment infrastructure. Talk to customers specifically about model behavior and consistency. Consider whether the company’s cost structure aligns with claimed AI capabilities—automation should enable superior unit economics, while manual labor should require linear scaling of costs.

- In acquisition agreements: Include specific representations and warranties about AI capability claims, model performance metrics, and absence of regulatory investigations. Require seller indemnification for any regulatory penalties or customer litigation related to false AI claims. Implement escrow arrangements that provide recourse if AI capabilities prove overstated post-acquisition.

- Post-acquisition: Conduct independent technical assessment within 30 days of closing to validate claimed AI capabilities. Implement continuous model monitoring to verify that claimed performance metrics are achievable in production. If gaps emerge, execute immediate customer communication and remediation planning. Don’t assume that just because you’re the owner, the AI systems will improve—many fake AI systems don’t become genuine simply through ownership change.

- During exit preparation: Disclose AI capability limitations clearly to potential buyers and include support for their technical due diligence. Buyers will investigate AI capabilities thoroughly, and undisclosed limitations discovered during buyer’s due diligence will crush valuation and deal certainty. Transparency about technical capabilities and limitations preserves credibility and deal value.

The Path Forward: Building AI Due Diligence Capability

The persistence of AI washing in PE acquisitions reflects a broader transition period where AI has become sufficiently central to technology company valuations that deception has become lucrative, while PE firms have not yet built sufficient technical capability to detect deception. This gap will narrow over time as regulatory enforcement escalates, as PE firms build internal ML expertise, and as market experience accumulates around which AI companies succeed and which fail.

In the interim, PE firms that invest in building AI due diligence capability—through engaging specialized advisors, developing internal expertise, implementing rigorous validation frameworks, and demanding transparency from sellers—will successfully avoid the AI washing trap and capture the significant value available in genuine AI-driven businesses. Those that continue to rely on traditional financial and commercial due diligence while underestimating the need for specialized technical validation will continue experiencing expensive post-acquisition discoveries that AI capabilities were false, regulatory enforcement, customer churn, and value destruction.